When it comes to writing stories readers devour, it’s all about creating immediacy sentence by sentence. We can engineer a stellar plot line, dream up characters with compelling conflicts — all the broad strokes – but it’s the accumulation of small word choices that keep a reader spellbound.

Writing is all about the sentence.

Here’s the empowering thing about that:

We’re making choices every step of the way.

And an often overlooked choice is the verb.

Here are three ways to keep readers spellbound, right on the sentence level, simply by changing your verbs.

1. Minimize Weak To-Be Verbs

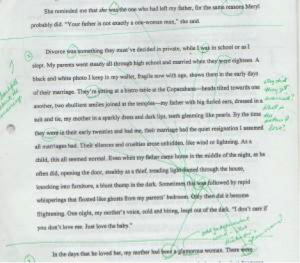

Years ago, in my first graduate writing workshop, Douglas Glover took his green pen to a page in my story, circled all the to-be verbs, then connected the circles to form this spider.

While I had fancied this passage pretty good at the time, the green spider web spotlighted the lackluster truth.

I riddled my prose with weak verbs.

Was, am, is, are, were, had been, would have tell us about a state of being, but lack action or meaning. Their only function is to link to a noun, adjective or phrase.

Compare this sentence…

The hill was steep.

with..

The building’s triangular shadow cut upward across the hill like a wedge.

To-be verbs are inert.

They make your sentences flabby. And your scenes dismissible.

You can’t banish them completely. And, yes, they are grammatically correct. But when you habitually default to them, the reader can’t enter the world of your story.

That’s because to-be verbs don’t create images. And without images, the reader can’t have a visceral, emotional response to your story.

2. Replace Mundane Verbs With Active, Descriptive Verbs

Generic verbs like, walk, run, lift, etc. make good starter verbs in our early drafts. But revision is all about invigorating each sentence, making scenes more muscular and potent.

Verbs shouldn’t just walk. They should saunter, sashay, galumph.

Not just run, but dash.

Not lift, but boost, or hoist.

Not just circle around, but curlicue.

Active verbs energize your writing. And describe more vividly than any adjective.

3. Be Precise

The more precise and actionable your verbs, the more arresting each sentence.

Does the sun shine on the hillside? Or slant?

Does the car race around the corner? Or careen?

Do crickets chirp in the dusk? Or sizzle?

Check out this passage from Denis Johnson’s story, Car Crash While Hitchhiking. I’ve highlighted the active verbs in red, the to- be verbs in green.

… I rose up sopping wet from sleeping under the pouring rain, and something less than conscious, thanks to the first three of the people I’ve already named–the salesman and the Indian and the student–all of whom had given me drugs. At the head of the entrance ramp I waited without hope of a ride. What was the point, even, of rolling up my sleeping bag when I was too wet to be let into anybody’s car? I draped it around me like a cape. The downpour raked the asphalt and gurgled in the ruts. My thoughts zoomed pitifully. The traveling salesman had fed me pills that made the linings of my veins feel scraped out. My jaw ached. I knew every raindrop by its name. I sensed everything before it happened.

Notice the precision: draped, raked, gurgled, zoomed, scraped, ached. Intentional choices, sentence by sentence, verb by verb.

18 active, descriptive verbs to a mere 4 weak to-be verbs.

My friend and poet, Anique Taylor calls this part of the revision process “sculpting” – getting rid of the flab, tightening each sentence to it’s most vibrant effect.

Your turn.

1. Take a passage or page from one of your works in progress. Circle all the verbs.

Do the math. How many weak to-be verbs?

2. Wherever possible, replace to-be verbs with an active verb.

Do the math again. This time, you should have a higher ratio of active to weak.

3. Circle your active verbs. Are any too generic? Where can you be more precise?

Keep sculpting to give each sentence more vigor.

The great and surprising thing about this revision exercise is that it invites you to think about your story in an entirely different way. It forces you to go deeper into the emotional structure, to reach for something more concrete, something that lives and breathes in the world of the real.

This sculpting technique is all about play and experimentation.

Give it a go.

Then if you’re up to it, share your newly sculpted sentences in the comments below.